Stories For Solidarity from Content Magazine on Vimeo.

Mikomi Yoshikawa-Baker, “Miko,” desperately wanted to protest the murder of George Floyd. But, given the police’s rampant use of tear gas and rubber bullets, she also wanted to keep herself and her young daughter away from the crowds. So she looked around the downtown neighborhoods, noticed all the boarded-up windows, and discovered the best way to join the movement—by calling in an army of creatives, buying up gallons of paint, and depicting powerful antiracist messages on the ubiquitous blank lumber.

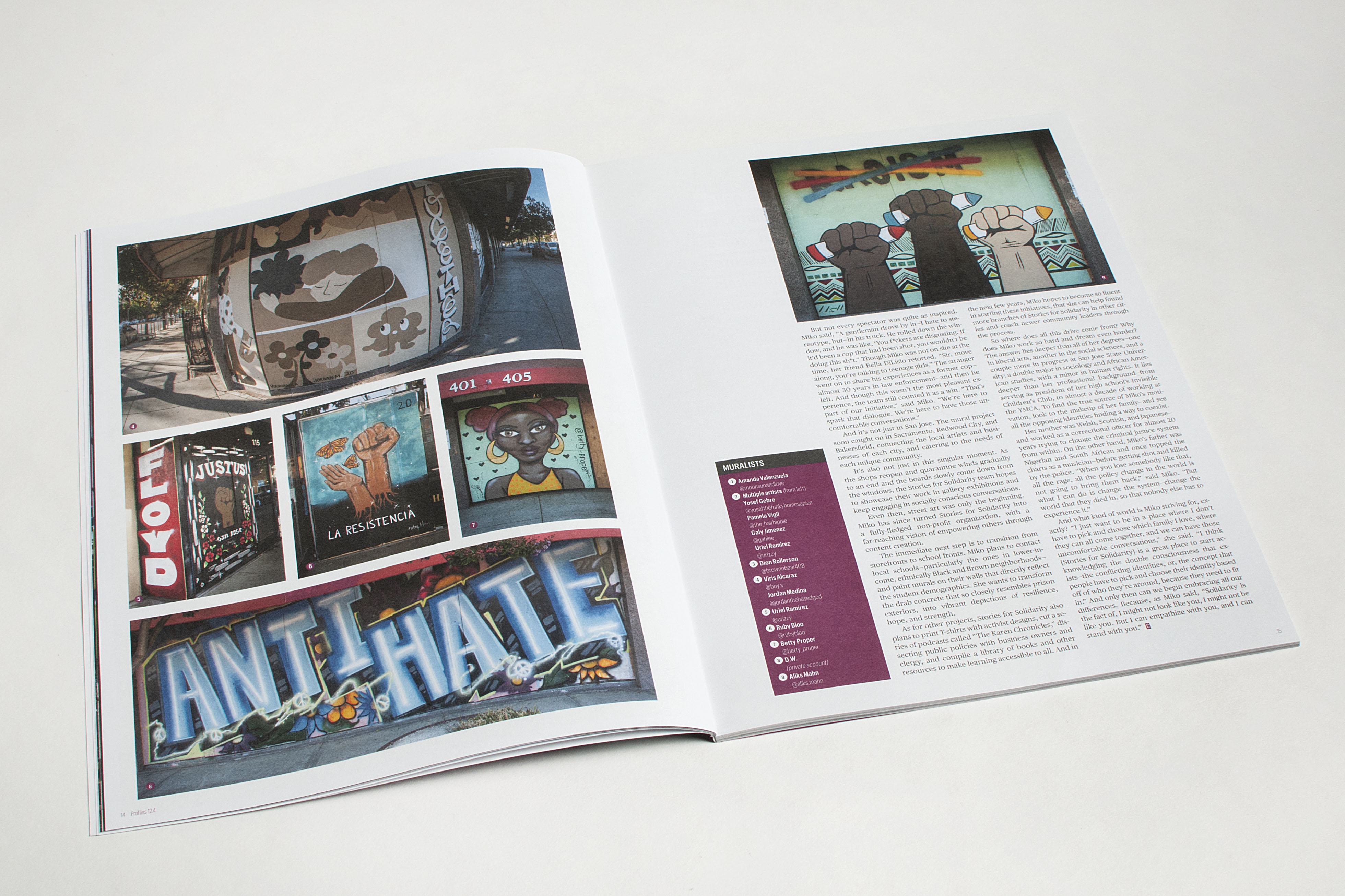

First, Miko contacted her artist friend Andrew Gonzalez, who then connected the Cinnaholic with tattooist Your Homeboy Harv and graphic designer Dion Rollerson. Harv painted a brown-skinned Bart Simpson leaving playful tags on the bakery walls, and Rollerson created a glowing portrait of Colin Kaepernick under the banner, “United We Kneel.” Then, while assisting on this initial project, Miko went on a coffee run and bumped into a Philz franchise owner. She pitched the idea of painting their boards and won approval on the spot—resulting in a series of geometric shapes, grinning faces, and motivational messages designed by Fernando Force 129 and Andrew Gonzalez in front of

the coffee shop.

From there, Miko didn’t really have to convince local enterprises anymore. They started calling her. All through Paseo Plaza, then Santa Clara Street, all the way down to 11th Street—everybody wanted to contribute their storefront to the cause. Some owners gave total creative freedom. Others asked for a particular theme. The Korean proprietors of La Lune Sucrée, for example, requested an image to represent Yellow Peril—a tiger, painted by Alicia Nodarei, to express solidarity between those of Asian and Pan-African descent.

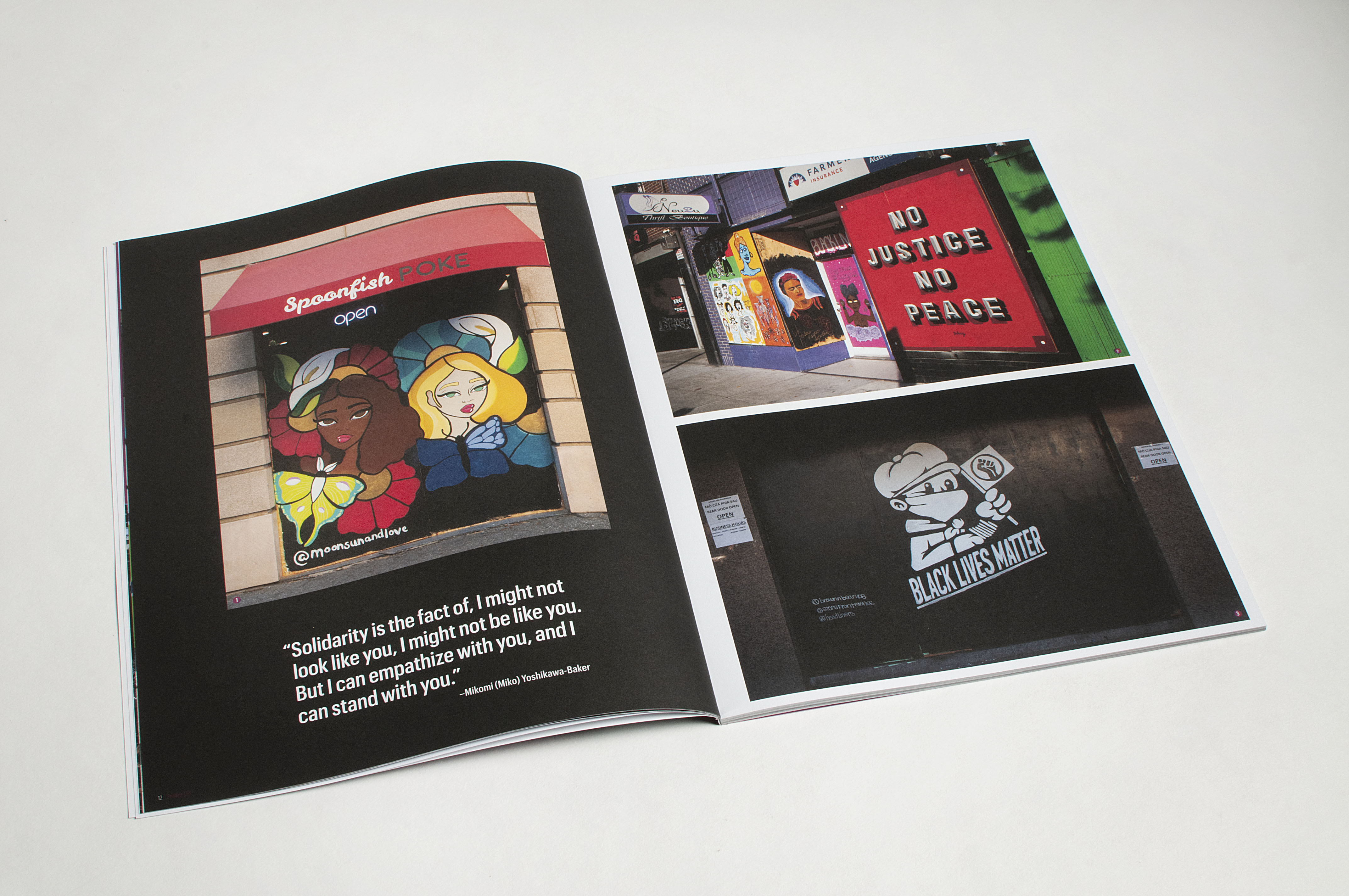

In return, the restaurant owners made sure to show their thanks. Spoonfish plied Miko and her team with free poké bowls; La Lune Sucrée offered fresh watermelon and homemade bread; Philz provided much-needed business advice, as the grassroots effort—now operating as Stories for Solidarity—navigated a sudden flood of attention. Every gesture and every day was full of mutual care and appreciation. As Miko said, “[This initiative] gained a lot of support really quickly, because the owners felt the intention and the love behind this project.”

“Solidarity is the fact of, I might not look like you, I might not be like you. But I can empathize with you, and I can stand with you.” _Mikomi Yoshikawa-Baker

And it wasn’t just the shop owners who responded so well—it was also, of course, the people on the street. They took pictures, asked questions, or rode by with one fist raised in the air. Sometimes the reactions ran even deeper. Miko recounted her favorite success story, “This white family happened to be walking past, and the kids loved the artwork. And the parent used it as a teachable moment, to then explain to her kids what Juneteenth is, and why it happened, and why a bunch of kids were making these paintings. So that was like, “Wow!” For us, in terms of our mission for creating solidarity through art, sparking emotion, having dialogue—that just kind of hit the nail on the head for what we were trying to do.”

But not every spectator was quite as inspired. Miko said, “A gentleman drove by in—I hate to stereotype, but—in his truck. He rolled down the window, and he was like, ‘You f*ckers are disgusting. If it’d been a cop that had been shot, you wouldn’t be doing this sh*t.” Though Miko was not on site at the time, her friend Bella DiLisio retorted, “Sir, move along, you’re talking to teenage girls.” The stranger went on to share his experiences as a former cop—almost 30 years in law enforcement—and then he left. And though this wasn’t the most pleasant experience, the team still counted it as a win. “That’s part of our initiative,” said Miko. “We’re here to spark that dialogue. We’re here to have those uncomfortable conversations.”

And it’s not just in San Jose. The mural project soon caught on in Sacramento, Redwood City, and Bakersfield, connecting the local artists and businesses of each city, and catering to the needs of each unique community.

It’s also not just in this singular moment. As the shops reopen and quarantine winds gradually to an end and the boards slowly come down from the windows, the Stories for Solidarity team hopes to showcase their work in gallery exhibitions and keep engaging in socially conscious conversations.

Even then, street art was only the beginning. Miko has since turned Stories for Solidarity into a fully-fledged non-profit organization, with a far-reaching vision of empowering others through content creation.

The immediate next step is to transition from storefronts to school fronts. Miko plans to contact local schools—particularly the ones in lower-income, ethnically Black and Brown neighborhoods—and paint murals on their walls that directly reflect the student demographics. She wants to transform the drab concrete that so closely resembles prison exteriors, into vibrant depictions of resilience, hope, and strength.

As for other projects, Stories for Solidarity also plans to print T-shirts with activist designs, cut a series of podcasts called “The Karen Chronicles,” dissecting public policies with business owners and clergy, and compile a library of books and other resources to make learning accessible to all. And in the next few years, Miko hopes to become so fluent in starting these initiatives, that she can help found more branches of Stories for Solidarity in other cities and coach newer community leaders through the process.

So where does all this drive come from? Why does Miko work so hard and dream even harder? The answer lies deeper than all of her degrees—one in liberal arts, another in the social sciences, and a couple more in progress at San Jose State University: a double major in sociology and African American studies, with a minor in human rights. It lies deeper than her professional background—from serving as president of her high school’s Invisible Children’s Club, to almost a decade of working at the YMCA. To find the true source of Miko’s motivation, look to the makeup of her family—and see all the opposing identities finding a way to coexist.

Her mother was Welsh, Scottish, and Japanese—and worked as a correctional officer for almost 20 years trying to change the criminal justice system from within. On the other hand, Miko’s father was Nigerian and South African and once topped the charts as a musician—before getting shot and killed by the police. “When you lose somebody like that, all the rage, all the policy change in the world is not going to bring them back,” said Miko. “But what I can do is change the system—change the world that they died in, so that nobody else has to

experience it.”

And what kind of world is Miko striving for, exactly? “I just want to be in a place where I don’t have to pick and choose which family I love, where they can all come together, and we can have those uncomfortable conversations,” she said. “I think [Stories for Solidarity] is a great place to start acknowledging the double consciousness that exists—the conflicting identities, or, the concept that people have to pick and choose their identity based off of who they’re around, because they need to fit in.” And only then can we begin embracing all our differences. Because, as Miko said, “Solidarity is the fact of, I might not look like you, I might not be like you. But I can empathize with you, and I can stand with you.”

storiesforsolidarity.com

Instagram: storiesforsolidaritysj, mikomikaelani

Article originally appeared in Issue 12.4 “Profiles”

Image Credits:

1. Miko Yoshikawa-Baker, CEO/Founder

2. Aliks Mahn, @aliks.mahn

3. Christopher Lee, COO

4. Viris Alcaraz @boy.s & Jordan Medina, @jordanthebasedgod

5. Nate Lopez, PR Coordinator

6. Dion Rollerson, Co-Creative Director

7. Dion Rollerson, @brownnbear408

8. Dijorn Anderson, Web Design

9. Uriel Ramirez, @urizzy