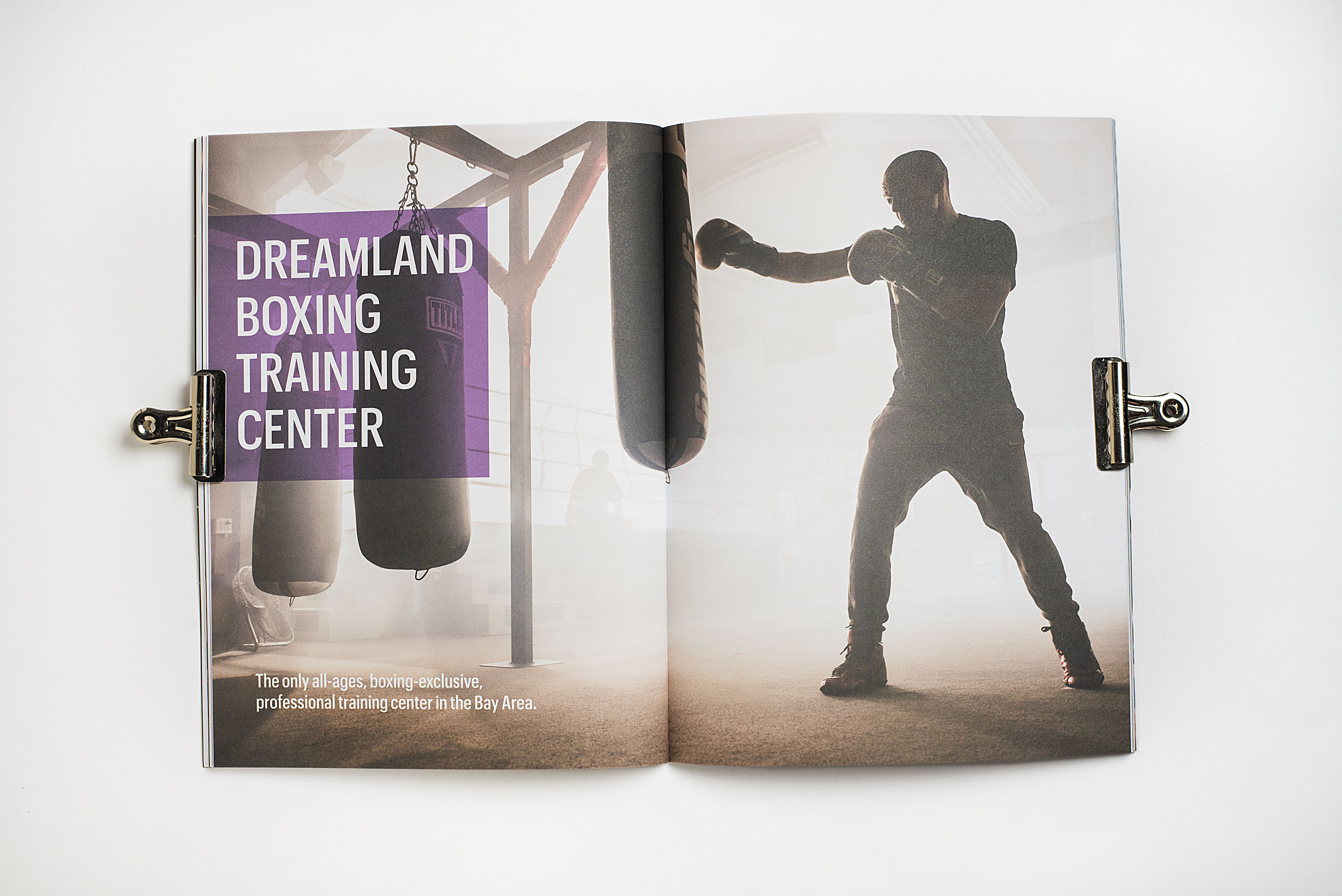

Search online for a San Jose gym that offers boxing, and you’ll find dozens that advertise this. Few are boxing exclusive. None have the Dreamland Boxing Training Center’s credentials. Dreamland is one of only four Bay Area gyms that can turn an amateur boxer into a licensed professional. The others are in San Francisco, Oakland, and San Mateo. Dreamland is the only gym in Santa Clara County that’s certified by USA Boxing, the national governing body for Olympic-style amateur boxing. Dreamland’s lead trainer, Jesse Huerta, is the only trainer in the county that’s licensed as a professional trainer by the California Athletics State Commission.

It’s hard to get Huerta to talk about how important Dreamland is to Bay Area boxing. He’d rather tell you how diverse Dreamland’s membership is and how its programs help its members and their families. Three licensed professional boxers train at Dreamland. Its co-ed boxing team competes against San Jose Police Activities League and other youth teams around the Bay, and its members range from eight years old to 75.

Walk into an evening youth class, and you’ll see engaged girls and boys from eight to 17 years old doing a hard workout. Their parents and younger siblings are seated comfortably nearby. Huerta’s wife, Gina, is “Momma G.” She’s at the door and knows everyone. She makes the vibe friendly and inclusive.

“This is what Dreamland is all about,” says Huerta. Dreamland is a safe, supportive environment where the skills needed for life are taught and practiced. By training to box, says Huerta, youths learn discipline and goal setting. They gain confidence and patience. “Life is tough like in the boxing ring,” Huerta says. “It’s how you overcome it, and that’s what we’re teaching here.”

Chris “the Warrior” Washington exemplifies what Dreamland teaches. He’s an undefeated professional boxer who competes as a junior middleweight. He grew up in South San Jose and came to Dreamland as a youth. He says he was extremely shy and at risk for getting into big trouble. Washington wanted to box because of the happy times he had watching prizefighting on television with his dad and brothers. “We loved it,” says Washington. “We used to watch it, and then we’d fight inside and outside with our friends.”

Washington befriended Dreamland’s founders, David “Sarge” Neeleman and his wife, Maria. They became Washington’s mentors. Sarge had over 50 years of boxing experience, first as a fighter and then as trainer. After Sarge retired from a career in construction, the Neelemans wanted to start a 501(c)(3) charity. Their vision was of a community center that would use the sport of boxing to help youths and their families. In 2004, the Neelemans used their life savings to open Dreamland. Maria’s father, a former boxer, named Dreamland after San Francisco’s Dreamland Auditorium.

The Dreamland Auditorium was a well-known venue that featured boxing and concerts from the early 1900s through the 1950s. “It’s hard to imagine,” says Bay Area boxing historian Eddie Muller, “how popular boxing was in the Bay Area before there were major league sports west of the Rockies.” Through the 1950s, San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose had boxers whose fights sold out at civic auditoriums and the Dreamland Auditorium. Before World War II the Dreamland Auditorium also functioned as a community center. It offered ice skating, roller skating, boxing, and other activities for youths. Maria’s father and his friends enjoyed the community center activities and the professional and amateur boxing shows that were offered.

Through the mid-1960s, most Bay Area high schools as well as Stanford University, Santa Clara University, and San Jose State had boxing clubs. By the late 1960s, most school programs ended, largely due to the public’s shrinking interest in boxing as the San Francisco Giants, 49ers, and Golden State Warriors took center stage. The Dreamland Auditorium reflected this change. It was sold to Bill Graham in 1971. He renamed it “Winterland” and turned it into a legendary venue for music shows. Muller mourns the loss of school boxing programs. “The discipline that boxing takes,” says Muller, “positively affects people throughout their entire lives.”

Today, the Dreamland Boxing Training Center positively affects youths with its open-door membership policy and code of conduct. Membership fees are waived for those without funds. The code of conduct requires members to be respectful, to dress properly, and to use polite language. “If you give them something constructive to do, structure, and opportunities to socialize,” says Neeleman, “it helps them to grow as secure individuals who help others.”

Neeleman says Washington the youth developed into an honorable, respectable, and righteous man as he trained with Sarge. He learned to believe in himself. Both Neeleman and Washington say that Sarge was demanding and tough, yet tender. “Sarge often said,” recalls Neeleman, “whatever you put into it, you get out of it.”

Washington says he’s gotten a lot more out of Dreamland than his love of the sport and his undefeated record. “Whenever I come to the gym,” says Washington, “I’m always happy, and I learned to talk to people.” He recalls a troubled time when Jesse Huerta was there for him, offering support and good advice. “It’s like a family,” says Washington. “It was like that with Sarge; it’s like that with Jesse still.”

“I believe I can be champion. That’s why I’m here.” –Chris Washington

In 2013, due to an illness, Sarge asked Jesse to run Dreamland’s day-to-day operations and to train its amateur and professional boxers. Huerta had been a competitive boxer in the 1980s. He trained at boxing promoter Joe Gagliardi’s Garden City Boxing Club. It was located in San Jose on Santa Clara Street on the second floor of Hank Coca’s furniture store. In those days, Joe Gagliardi’s fights filled civic auditoriums throughout Northern California, as well as the Circle Star Theater and the Oakland Coliseum Complex, with fans. Boxing events at the San Jose Civic Auditorium were standing room only when Garden City Boxing Club members Albert Romero, Joaquin “Pinky” Rivera, and Stevie “Double Barrel” Romero fought. When Huerta found that he liked training fighters more than competing, he became a professional trainer while he raised his family and worked as a probation counselor at Santa Clara County’s Juvenile Hall. In 2015, after Sarge passed away, the Huertas took over Dreamland as its executive directors and financial managers.

Financial support comes from membership fees, generous members, and TITLE Boxing. A generous TITLE Boxing discount enables Dreamland to provide gloves to those who can’t afford them. TITLE Boxing sponsors the Dreamland Masters World Championship. The master amateur division is for boxers 35 years old or older. This annual tournament is sanctioned by USA Boxing and the Northern California Local Boxing Commission. It attracts competitive boxers from around the world, and it’s part of Dreamland’s vision of all-ages inclusion.

The Huertas have kept the Neeleman’s vision and have dedicated their lives to preserving it. Jesse Huerta says boxing isn’t a brutal combat sport or a ticket to championship riches. It’s a proven way to guide youths to a positive future. Washington says he initially wanted the glamour and wealth that goes with a boxing championship, but his goals have changed. Now he wants to do things for his family and the youths he trains at Dreamland. “I believe I can be champion,” says Washington. “That’s why I’m here; it’s good here.”

Dreamland Boxing

Facebook: dreamlandboxing

thewarriorwashington

Instagram:

dreamlandboxing

realchriswashington

Dreamland Training Center: (408) 412-8231

2047 Woodard Rd, San Jose, CA 95124 USA

This article originally appeared in Issue 11.3 “Perform”