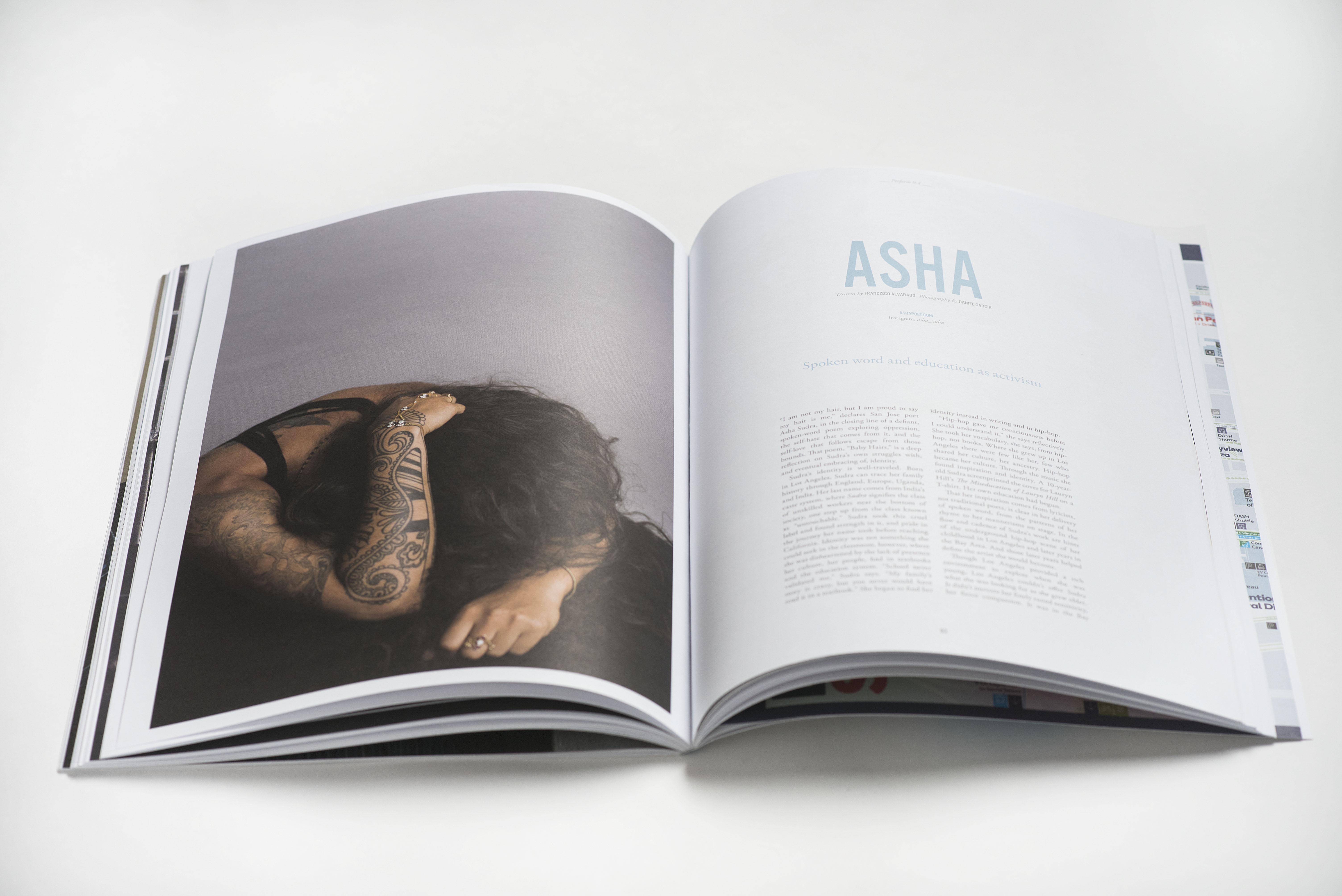

AAsha’s identity is well-traveled. Born in Los Angeles, Asha can trace her family history through England, Europe, Uganda, and India. Her last name comes from India’s caste system, where Sudra signifies the class of unskilled workers near the bottom of society, one step up from the class known as “untouchable.” Asha took this cruel label and found strength in it, and pride in the journey her name took before reaching California. Identity was not something she could seek in the classroom, however, where she was disheartened by the lack of presence her culture, her people, had in textbooks and the education system. “School never validated me,” Asha says. “My family’s story is crazy, but you never would have read it in a textbook.” She began to find her identity, instead, in writing and in hip-hop.

“Hip-hop gave me consciousness before I could understand it,” she says reflectively. She took her vocabulary, she says, from hip-hop, not books. Where she grew up in Los Angeles there were few like her, few who shared her culture, her ancestry. Hip-hop became her culture. Through the music she found inspiration and identity. A 10-year-old Asha screenprinted the cover for Lauryn Hill’s The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill on a t-shirt. Her own education had begun.

“Hip-hop gave me consciousness before I could understand it.”

That her inspiration comes from lyricists, not traditional poets, is clear in her delivery of spoken word, from the patterns of her rhyme to her mannerisms on stage. In the flow and cadence of Asha’s work are hints of the underground hip-hop scene of her childhood in Los Angeles and later years in the Bay Area. And those later years helped define the artist she would become.

Though Los Angeles provided a rich environment to explore when she was young, Los Angeles couldn’t offer Asha what she was looking for as she grew older. It didn’t nurture her finely tuned sensitivity, her fierce compassion. It was in the Bay Area, where she moved to in 2006, that she found a community she could identify with, a community that inspired her. “The artist community that I’ve found specifically here in San Jose and Oakland and San Francisco,” she says with spirit, “is the community I’ve been looking for my whole life, the friends I’ve been looking for my whole life.” Asha’s work sometimes features a subtle homage to this community and to the friends who inspired her to add to her other artistic pursuits the art of spoken word. “My friends are crazy-talented,” Asha laughs.

And just as her friends inspire her, Asha also inspires others in her role as educator. In her day job, Asha works as an eighth grade teacher in Campbell, and she uses her poetry to relate to students and to help them find their own identities. “I’m an educator,” she says, “because my story wasn’t validated.” Her objective with her students is to explore their identities and then to affirm those identities. Asha utilizes a “windows and mirrors” approach. “Whatever we’re doing, you see yourself as in a mirror, or it’s a window into someone else’s perspective to which you haven’t been exposed yet,” she explains. Her dream is to open a K–12 school that is safe and inclusive, that embraces diversity, that nurtures the identities of its students. “I believe in the kids,” Asha says simply.

In her life, in her work, identity has been key. Discovering that identity, constructing that identity, has been a lifelong journey—and her passion. This passion is embedded in her art; it’s the driving force behind her life goals. This passion has taken her on tours abroad, to the forefront of the historic Women’s March in San Jose, to the classrooms of the South Bay. This passion is the reason Asha plans to create an interactive, multimedia exhibit that details her family’s story. Asha Sudra’s search for identity hasn’t ended. Her work as artist, educator, revolutionary continues.

ASHA

instagram: asha_sudra

This article originally appeared in Issue 9.4 “Perform”