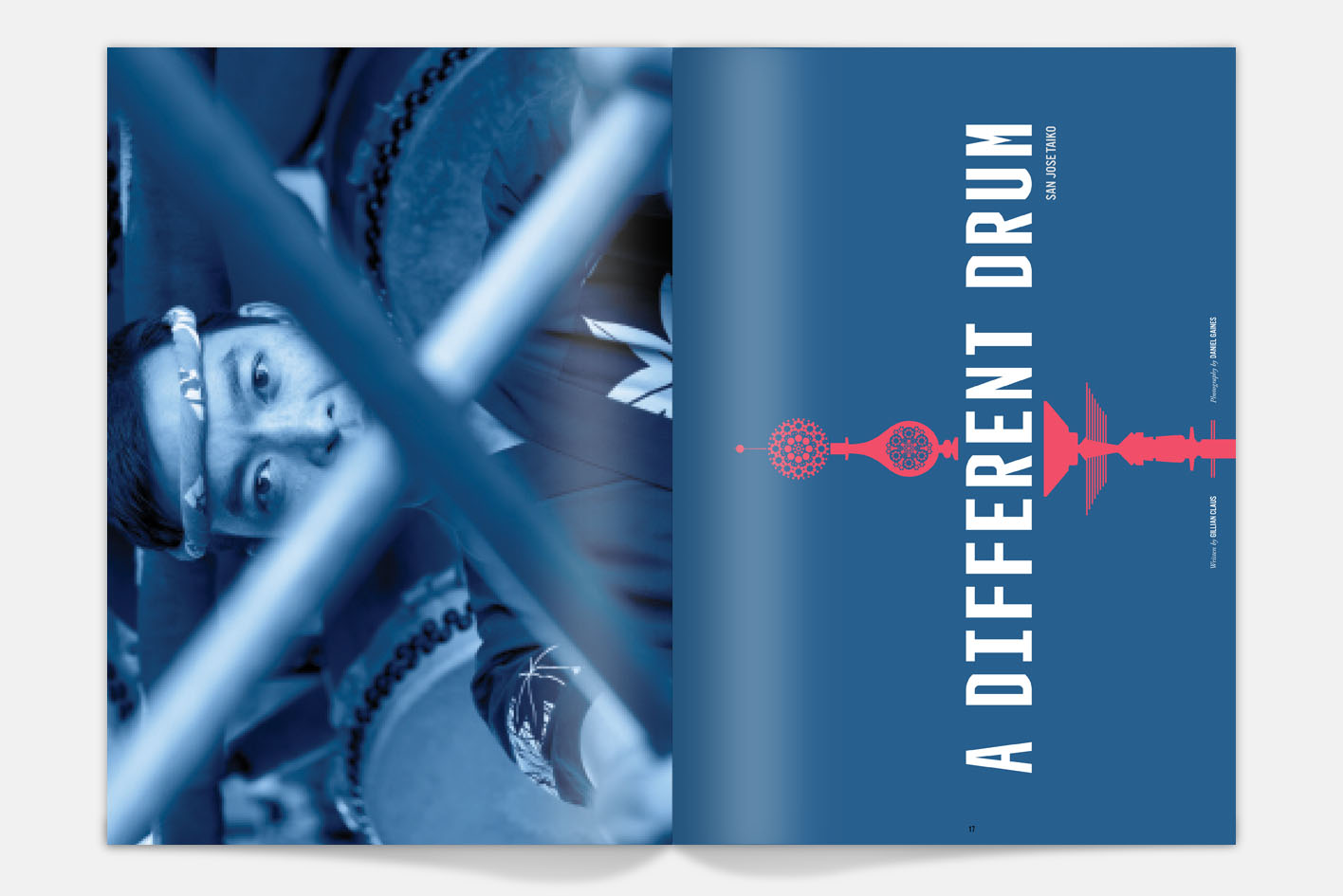

For ten years I have heard booming thunder during springtime in downtown San Jose. It wakes me up and makes the windows hum. The sound motivates me to slip on some sandals and hustle down to Japantown. That thunder means San Jose Taiko, every bit as powerful and exciting as the first day I heard them.

But what makes it possible to shake the windows from three blocks away? How do you get so much sound from a drum? Is it the drum or the drummer that generates the power to rattle windows and make dogs bark?

To find the answers to these questions, I headed to San Jose Taiko’s rehearsal space in an old warehouse on Montgomery Street. It was cold in the empty studio and the cloudy skies made the room dark. As company member Meg Suzuki emerged from the towering racks of wooden drums, she detailed the effect that rapid variations in temperature can have on the instruments. The sound will vary greatly especially if exposed to high humidity, something to consider as they haul 3500 pounds of drums to a local festival or halfway across the world.

Taiko is the Japanese name for two-headed drums, mounted on upright stands, ranging in diameter from 12 inches to 12 feet. They have an iron ring for lifting and carrying in processions. Traditionally in Japanese theatre, they provided sound effects with special strokes to portray (rather than imitate) rain, snow and wind. The story goes that jazz drummer Daihachi Oguchi invented modern taiko style by arranging the instruments in the temple like a western drum set and creating a dramatic folk-jazz crossover.

Unlike the customary instruments carved from a trunk of Japanese oak, the drums Meg hauled out onto the warehouse floor had a wine-barrel construction. Typical of North American taiko, staves of wood are bound together to make the body of the drum. Developed by Kinnara Taiko in Los Angeles in the late 1960s, this drum was lighter and much less costly to ship. This revolutionary design made it easier for groups to form, allowing taiko to spread across North America. San Jose Taiko began in 1973.

Since it uses fewer trees, the barrel design has caught on back in Japan and San Jose Taiko is now collaborating with top percussion manufacturer Pearl on a prototype taiko drum. Artistic director Franco Imperial explained that although the group once made their own drums, they now purchase from master craftsmen like Mark Miyoshi in Mount Shasta and Kato Drums from Concord. San Jose Taiko hopes that their drums will last forever, and indeed by caring for their instruments, they still have drums nearly as old as the group itself.

It is hard to imagine that an old cowhide could produce such a mighty reverberation. The leather skins that cover both ends of the drums are the key to tuning the drums. It once took five men to stretch the cowhide over the barrels to create the taut surface and nail the heads down, but today dowels and a series of car jacks accomplish the job. The skins are replaced every one to two years depending on wear and tear.

And how do you make the drums thunder? Each size of taiko has special-sized wooden bachi (drumsticks) and each player has their own pair for each type of drum. The left-hand plays a lighter “female” stroke while the right makes a heavy “male” stroke in the center of the drumhead.

Becoming a taiko member is no easy committment, both in strength and time. The audition process alone takes one year, leading to a further 12-month apprenticeship. The 18 company members also compose much of the original music that they perform. Each group is different, but Franco stressed that for San Jose Taiko, “it doesn’t matter what ethnicity you are as long as you have the proper attitude and skill.” Members range in age from 20 to 40 and perform nationally as well as in Japan, Mexico, Canada, Italy, and the UK.

Back home, that power extends into the community with outreach programs. First of its kind in the country, San Jose Taiko Conservatory is expanding upon the company mission to enrich the human spirit and connect people beyond cultural and demographic boundaries. All ages can participate via a Junior Taiko workshop, an adult class or a free performance at festivals like Nikkei Matsuri in Japantown.

Stepping out of the warehouse to the echo of the drums, I looked forward to the day when I will again hear them rattling my windows. In the words of Daihachi Oguchi, “In taiko, man becomes the sound. In taiko, you can hear the sound through your skin.”

San Jose Taiko www.taiko.org

Article originally appeared in Issue 4.1 Power 2012

(Print SOLD OUT)