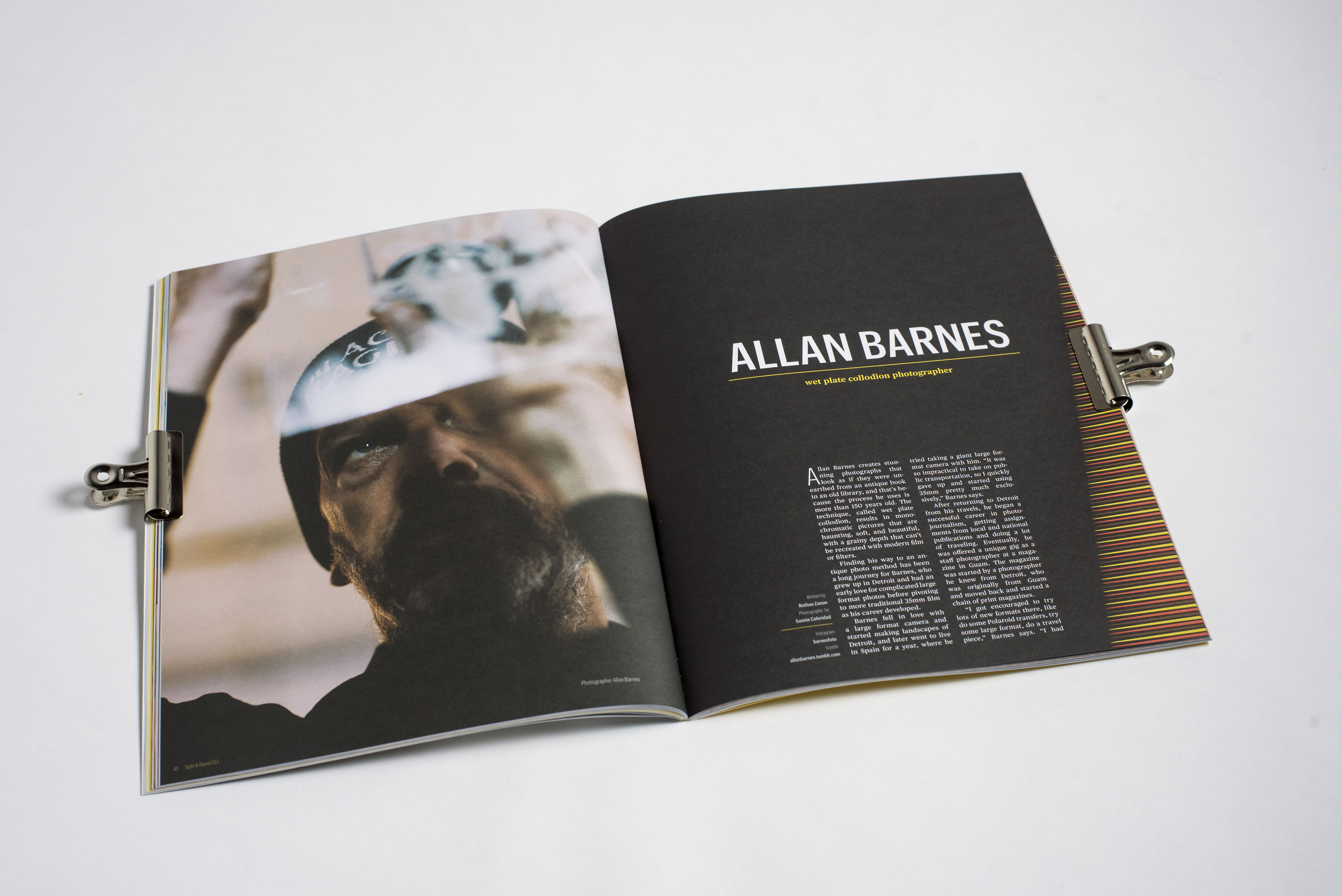

Allan Barnes creates stunning photographs that look as if they were unearthed from an antique book in an old library, and that’s because the process he uses is more than 150 years old. The technique, called wet plate collodion, results in monochromatic pictures that are haunting, soft, and beautiful, with a grainy depth that can’t be recreated with modern film or filters.

Finding his way to an antique photo method has been a long journey for Barnes, who grew up in Detroit and had an early love for complicated large format photos before pivoting to more traditional 35mm film as his career developed.

Barnes fell in love with a large format camera and started making landscapes of Detroit, and later went to live in Spain for a year, where he tried taking a giant large format camera with him. “It was so impractical to take on public transportation, so I quickly gave up and started using 35mm pretty much exclusively,” Barnes says.

After returning to Detroit from his travels, he began a successful career in photojournalism, getting assignments from local and national publications and doing a lot of traveling. Eventually, he was offered a unique gig as a staff photographer at a magazine in Guam. The magazine was started by a photographer he knew from Detroit, who was originally from Guam and moved back and started a chain of print magazines.

“I got encouraged to try lots of new formats there, like do some Polaroid transfers, try some large format, do a travel piece,” Barnes says. “I had morphed into a 35mm photojournalist guy.” He returned to large format and began the journey he’s on now—working large format.

Barnes’s passion for specific film stock and the technical details around the process of photography comes through in conversation with him, and it’s clear that he enjoys challenging himself through his work. “I was starting to do a lot of experimental work with Polaroid material,” he recalls. “The doomsday clock for Polaroid was ticking as digital became the new technology.” His film of choice was Polaroid Type 55—black and white. “It was amazing film,” he explains. “It gave you both a negative and a positive, so if you were doing travel stuff you could take somebody’s picture and give them a copy, and then you had the negative. It was beautiful film, so I really was in love with that.”

But Polaroid went bankrupt, eliminating his favorite film stock. Meanwhile, the journalism business was also changing, and Barnes found himself wanting to explore his artistic side. Inspired by work from photographer Robert Maxwell, he immersed himself in learning wet plate techniques, and in 2006, he moved to Los Angeles, into a giant shared loft with a bunch of other artists.

“I started doing this antique process, collaborating with clothing designers and circus performers, clowns, magicians, musicians–there’s just a really amazing pool of people. So I started doing a lot of portraiture in this space behind my studio,” says Barnes. “Photography has taken me to all these places [where] I might not have spent any time and taken me to events and introduced me to people. It has been a really good journey. You have this passport to be kind of an anthropologist/investigator.”

After developing his photos, Barnes scans and transfers the images to a digital format to clean up in Photoshop, merging his antique technique with modern technology. He has embraced Instagram and Tumblr for sharing his work.

“Technology is a banquet,” he says. “You can do these crazy old processes, but then you can enhance them with Photoshop and Lightroom and make inkjet prints of them. I just made my first inkjet print of one of the pictures from yesterday and it’s gorgeous.”

Today, he teaches digital photography at Morgan Hill High School while living in San Jose, where his apartment doubles as his photo studio. He also teaches workshops on the wet plate technique at Harvey Milk Photo Center in San Francisco, temporarily on hold until after the pandemic.

“It’s such a fickle process, but when you get a good plate, it’s like random reinforcement–which is the way people get addicted to gambling.”

–Allan Barnes

Barnes came up to the Bay Area for a teaching job, but didn’t plan on living here. “I set my sights on Los Angeles, and it was a struggle. I had to reinvent myself,” he shares. “I was like, ‘Are you still a photographer if people don’t call you and offer you money to take pictures of things?’ Well, I’m still a photographer, and I’m still going to produce work; it just became my own journey instead of a journey inspired by people paying me to do stuff.”

Between teaching gigs, he has been exploring landscape photography, traveling up and down the coast to capture the stunning views that can be found across Northern California. But the antique technique doesn’t travel well. A mobile darkroom is required, as the negatives need to be developed quickly. His solution was to buy an RV to do the job, another example of his dedication to the craft.

“It’s intensely physical,” he explains. There is a lot of equipment involved, and it’s very slow. The exposure times are long and there’s all kinds of stuff that can go wrong. “It’s such a fickle process, but when you get a good plate, it’s like random reinforcement–which is the way people get addicted to gambling. You spend a lot of time making a picture, and when it comes out really good, you’re holding it in your hand; it’s grains of silver, it’s tangible.”

Instagram: barnesfoto

Tumblr: allanbarnes.tumblr.com

Featured in issue 13.2 “Sight and Sound,” Spring 2021