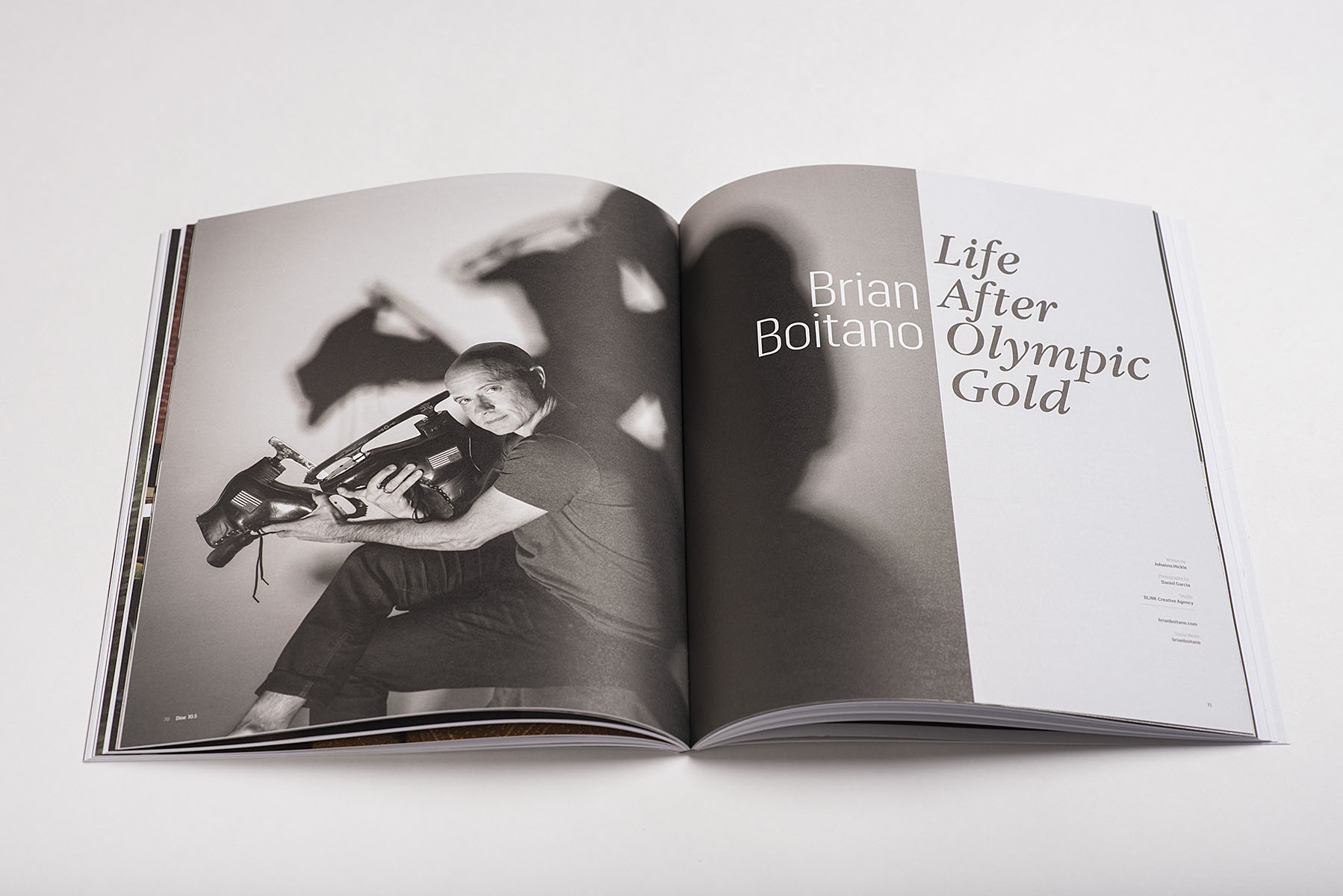

As Brian Boitano skates onto the ice, the psychological weight is colossal. “It’s like the microwave gets turned on,” he describes, “and you’re cooking from the inside out, ready to explode.” The roar of 20,000 throats tidal waves over him and washes across the Saddledome. The almost palpably solid feeling of 20,000 pairs of eyes latch onto the back of his neck like a grappling hook. He strikes an erect pose, made all the more commanding in a blue military uniform. Silence falls like an ax. The music swells. And Boitano’s skates stir to life.

That was 1988, and three decades later journalists continue to ask Boitano about the subsequent four minutes and thirty seconds of his life. After all, Calgary ’88 earned him an Olympic gold medal in men’s singles figure skating. Only one other American has achieved that status for the same event since. The media also senses—as they did in the days leading up to Boitano’s triumph—a noteworthy narrative. For starters, America was predicted to come in second. Brian Orser, flag carrier for that year’s host country, Canada, was favored for the win. However, both skaters had similar skill levels as well as matching military-themed song and costume choices. Reporters were soon championing the slogan “The Battle of the Brians.” Add to all this Boitano’s invention of a move called the “Tano Triple Lutz” (extending one arm overhead during jump and rotation), and you have an underdog, a rivalry, new advances to the sport—ingredients guaranteeing a recipe for success.

Boitano isn’t bothered by the constant requests to relive the routine that landed him top of the podium. “It was the culmination of everything,” he explains, “the culmination of all your childhood dreams and aspirations, the passion you have for it, the work that you put into it, all the people that had expectations for you, and the pressure you’re able to deal with.”

At 24, Boitano experienced a surreal moment of glory. “You know, at that moment, that nothing’s going to compare to that,” Boitano says. “That’s why it’s ingrained in my brain, so much that I remember every single emotion.” The unadulterated delight and overwhelming emotion that crossed his face after his flawless finish is proof enough the memory will never lose its potency. But that doesn’t mean life after Olympic gold is destined to be anticlimactic. Boitano feels incredibly fortunate for Calgary, and he credits it for the blessings that followed.

Whereas Orser’s decision to become a skating coach is a conventional one, Boitano’s chosen route has been a little less predictable. He’s gone from lacing up skates to tying on apron strings as a Food Network star and host. Though these fields are dissimilar in many ways, they do carry commonalities. “You layer the elements and you come up with a great recipe,” Boitano notes of both. “With cooking, it’s how a plate looks, how it smells, what the ingredients are, how they taste. With skating, the layers are choreography, music, costume.” Food is also a performance, he observes, appraised by friends

and family.

But there are also benefits to cooking that skating doesn’t offer. Renowned for his exacting technical accuracy on the ice, Boitano is surprisingly lenient with ingredients in the kitchen. “Skater Brian is literally precise and thinks of everything: every moment, every foot, every place,” he remarks. “Cooking Brian, is…I sort of made this pact with myself to not get too in my head about cooking. There’s not much difference between a handful of parsley and a handful and a half of parsley—so let’s not measure.” He enjoys going by instinct, imagining flavor combinations while brainstorming new recipes. “I like the freedom,” he confides with a smile.

Boitano’s playful synergy with food earned him his culinary debut with the Food Network. The title of the series—What Would Brian Boitano Make?—tips its hat to the song, “What Would Brian Boitano Do?” played during the cartoon South Park. It was informational, but it was also intimate (unique from the professional tone of the Network’s other shows at the time). In each episode, Boitano hosted events for his friends. These ranged from a sausage shindig for the Secret Society Scooter Club to a bacon-themed dinner for a women’s roller derby team. “It was a little bit irreverent, a little bit funny. I could show my goofy side, which was different from what everybody knew me as on the ice.”

Indisputably, skating will always be the passion ingrained deepest in Boitano’s heart. Until recently, he’s performed in shows and continues to swoop across the ice for recreation. “It’s the ultimate feeling of abandon,” he enthuses. “You’re traveling across the ice at 25 miles an hour, and then you’re throwing yourself in the air, and you’re landing on a thin blade with complete control. There’s this command of the energy in the air that you feel when you’re doing it. And when things are exactly how you want it, it’s this entire picture of, in your mind, perfection of the moment.” He’s held that fervor ever since he witnessed an Ice Follies show at eight and began pretending his roller skates were ice skates, his kidney bean-shaped patio a rink.

Nevertheless, Boitano doesn’t miss the excruciating pressure of competition. He identifies it as 95 percent a mental game. That critical inner voice is so palpable he nicknamed it “Murphy” after Murphy’s Law. “He’s saying ‘If anything bad can happen, it will happen.’ And you’re trying to punch Murphy down.” In contrast, Boitano takes his own pace with cooking and enjoys therapeutic late nights in the kitchen, testing new recipes and cocktails.

He also wasn’t very healthy as an athlete. At 16, he began regulating his diet with monastic devotion, quarantining himself from ice cream and his mom’s sandwiches. “I was always starving myself when I was training,” he acknowledges. Most meals consisted of baked potatoes with plain yogurt, salads with cooked pasta and diet dressing, and crackers with jam. He remembers wistfully watching food commercials on TV and writing them down in a “someday” list.

Perhaps most telling is one of Boitano’s fondest food memories. While training in an Alpine village one summer, he was submerged in a number of food firsts: buttery croissants, fluffy quiches, creamy fondue, and gooey raclette. “They eat what they eat,” he chuckles. “They don’t have diet jam and crackers.” He recalls with amusement his coach’s consternation when he returned to the States, stepping off the plane with a few extra pounds—and not the kind in his suitcase.

To Boitano, cooking is a memory maker, a love language expressed to friends and family. “You remember the food, and you remember the stories, and you remember the time you had,” he says before reminiscing about pizza parties hosted for relatives in Italy. (Try not to smile picturing 35 loud Boitanos all helping out in the kitchen.)

Undoubtedly, Boitano continues to embrace life after Olympic gold. But skating will always be an integral part of who he is. It’s in the straight-backed way he holds himself—ever the effortless poise of a skater. It’s in the 24-year-old gleam in his eyes as he talks about Calgary. It’s easy to picture him out there—his blades slicing across the rink in a crisp, satisfying whisper, the air favoring him a little more than the rest of us mortals as he spreads his arms and soars into jumps. But the playful chef is in there, too. You can imagine him surprising a dear friend with paella, or learning to make pasta from his Aunt Maria. In the end, he continues to mix and blend his energetic and spontaneous passions for life into new concoctions as he shifts off the ice and into the kitchen.

Social Media: brianboitano

Article originally appeared inIssue 10.5 Dine (Print SOLD OUT)