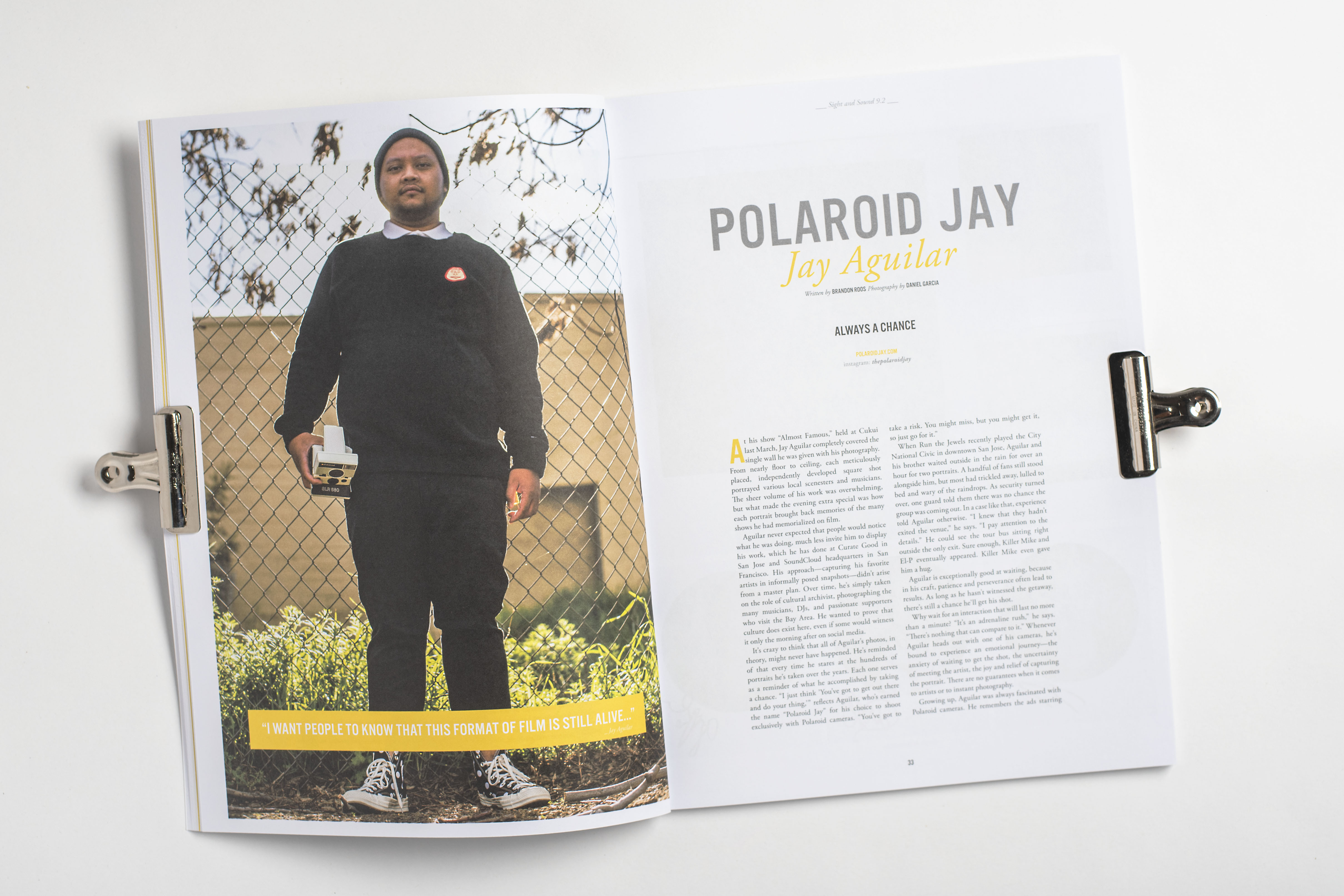

At his show “Almost Famous,” held at Cukui last March [Article orginally from 2017], Jay Aguilar completely covered the single wall he was given with his photography. From nearly floor to ceiling, each meticulously placed, independently developed square shot portrayed various local scenesters and musicians. The sheer volume of his work was overwhelming, but what made the evening extra special was how each portrait brought back memories of the many shows he had memorialized on film.

Aguilar never expected that people would notice what he was doing, much less invite him to display his work, which he has done at Curate Good in San Jose and SoundCloud headquarters in San Francisco. His approach—capturing his favorite artists in informally posed snapshots—didn’t arise from a master plan. Over time, he’s simply taken on the role of cultural archivist, photographing the many musicians, DJs, and passionate supporters who visit the Bay Area. He wanted to prove that culture does exist here, even if some would witness it only the morning after on social media.

“I want people to know that this format of film is still alive…” _Jay Aguilar

It’s crazy to think that all of Aguilar’s photos, in theory, might never have happened. He’s reminded of that every time he stares at the hundreds of portraits he’s taken over the years. Each one serves as a reminder of what he accomplished by taking a chance. “I just think ’You’ve got to get out there and do your thing,’ ” reflects Aguilar, who’s earned the name “Polaroid Jay” for his choice to shoot exclusively with Polaroid cameras. “You’ve got to take a risk. You might miss, but you might get it, so just go for it.”

When Run the Jewels recently played the City National Civic in downtown San Jose, Aguilar and his brother waited outside in the rain for over an hour for two portraits. A handful of fans still stood alongside him, but most had trickled away, lulled to bed and wary of the raindrops. As security turned over, one guard told them there was no chance the group was coming out. In a case like that, experience told Aguilar otherwise. “I knew that they hadn’t exited the venue,” he says. “I pay attention to the details.” He could see the tour bus sitting right outside the only exit. Sure enough, Killer Mike and El-P eventually appeared. Killer Mike even gave him a hug.

Aguilar is exceptionally good at waiting, because in his craft, patience and perseverance often lead to results. As long as he hasn’t witnessed the getaway, there’s still a chance he’ll get his shot.

Why wait for an interaction that will last no more than a minute? “It’s an adrenaline rush,” he says. “There’s nothing that can compare to it.” Whenever Aguilar heads out with one of his cameras, he’s bound to experience an emotional journey—the anxiety of waiting to get the shot, the uncertainty of meeting the artist, the joy and relief of capturing the portrait. There are no guarantees when it comes to artists or to instant photography.

Growing up, Aguilar was always fascinated with Polaroid cameras. He remembers the ads starring celebrities on TV, but never asked for one because they were too costly. He finally asked anyway in 2004, and his dad bought him a camera and four packs of film. He began shooting regularly in 2009 after he picked up an SX-70 with auto-focus from a coworker. Soon, he was scouring thrift stores for any model he could find and searching for deals on expired film on eBay. At one point, his collection included 40 cameras. It has since been whittled down to around 25, with six in regular working rotation. “I want people to know that this format of film is still alive, that you can go out and buy it and do it yourself,” he says.

After he lost his girlfriend, his photo crew, and his job in 2013, Aguilar began to pursue his craft with renewed focus. Capturing show portraits became his refuge, his therapy. “I didn’t think it would lead to super awesome stuff, but it did,” he says. “I feel like I’m in a better place now than I was when all that stuff happened.” He has since cultivated a following of over 4,500 followers on Instagram, and an online archive of more than 4,000 photos.

But Aguilar, as cultural archivist Polaroid Jay, has not just helped renew interest in instant photography, he has also created a link to the past. When thinking about the countless memories a single photo can evoke, he is reminded of times when his mom would ask if he remembered something and he would have no recollection until she produced a photo. Instantly, he’d be transported back to that moment. His own photography now provides that same refresher for an entire community. It also provides a tangible photo trail of timeless mementos in an increasingly digitized world.

Article originally appeared in Issue 9.2 Sight and Sound (Print SOLD OUT)