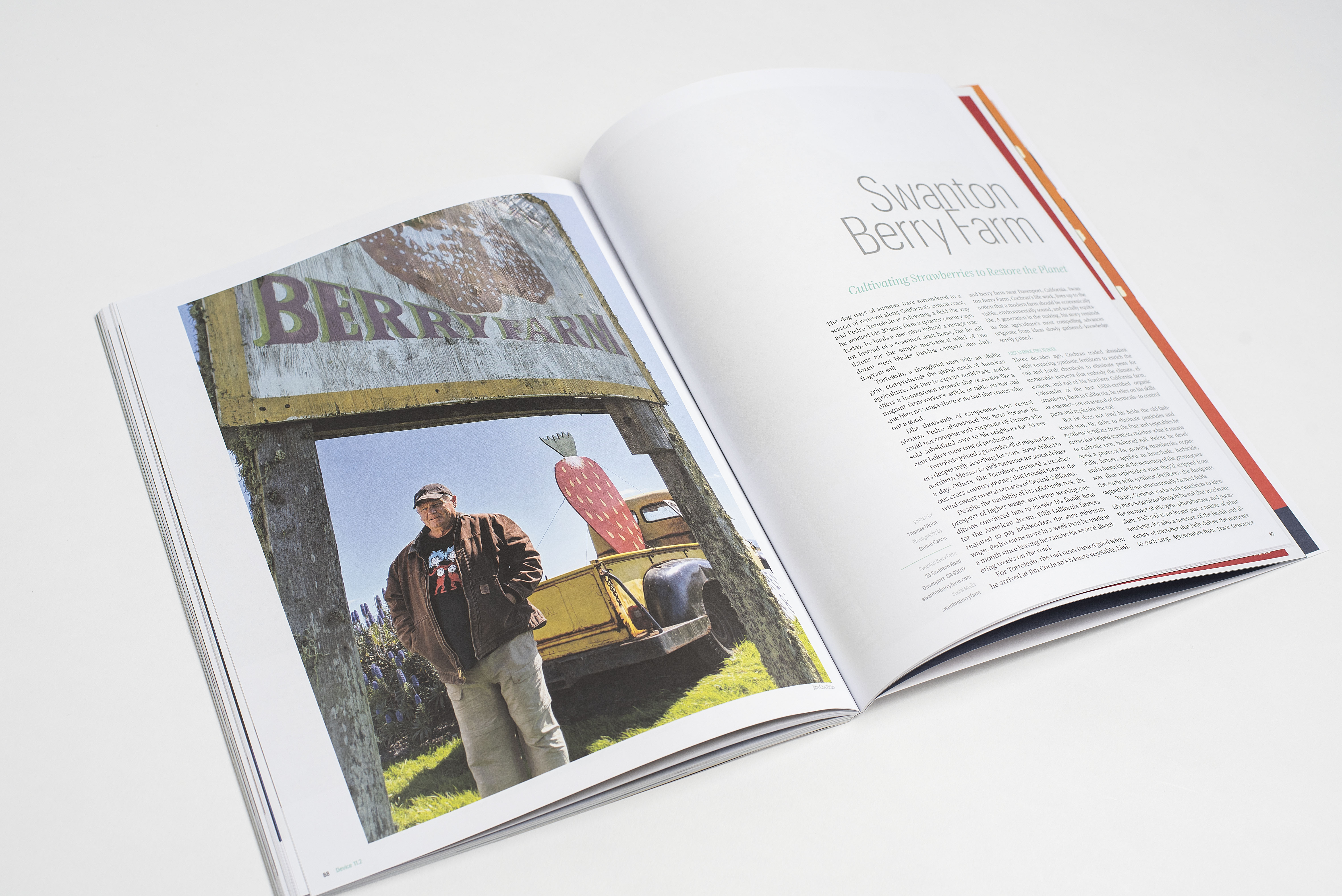

TThe dog days of summer have surrendered to a season of renewal along California’s central coast, and Pedro Tortoledo is cultivating a field the way he worked his 20-acre farm a quarter century ago. Today, he hauls a disc plow behind a vintage tractor instead of a seasoned draft horse, but he still listens for the simple mechanical whirl of two dozen steel blades turning compost into dark, fragrant soil.

Tortoledo, a thoughtful man with an affable grin, comprehends the global reach of American agriculture. Ask him to explain world trade, and he offers a homegrown proverb that resonates like a migrant farmworker’s article of faith: no hay mal que bien no venga–there is no bad that comes without a good.

Like thousands of campesinos from central Mexico, Pedro abandoned his farm because he could not compete with corporate US farmers who sold subsidized corn to his neighbors for 30 percent below their cost of production.

Tortoledo joined a groundswell of migrant farmers desperately searching for work. Some drifted to northern Mexico to pick tomatoes for seven dollars a day. Others, like Tortoledo, endured a treacherous cross-country journey that brought them to the wind-swept coastal terraces of Central California.

Despite the hardship of his 1,600-mile trek, the prospect of higher wages and better working conditions convinced him to forsake his family farm for the American dream. With California farmers required to pay fieldworkers the state minimum wage, Pedro earns more in a week than he made in a month after leaving his rancho for several disquieting weeks on the road.

For Tortoledo, the bad news turned good when he arrived at Jim Cochran’s 84-acre vegetable, kiwi, and berry farm near Davenport, California. Swanton Berry Farm, Cochran’s life work, lives up to the notion that a modern farm should be economically viable, environmentally sound, and socially equitable. A generation in the making, his story reminds us that agriculture’s most compelling advances originate from ideas slowly gathered—knowledge sorely gained.

First to Knock, First to Enter

Three decades ago, Cochran traded abundant yields that required synthetic fertilizers to enrich the soil and harsh chemicals to eliminate pests for sustainable harvests that embody the climate, elevation, and soil of his Northern California farm. Cofounder of the first USDA-certified organic strawberry farm in California, he relies on his skills as a farmer—not an arsenal of chemicals—to control pests and replenish the soil.

But he does not tend his fields the old-fashioned way. His drive to eliminate pesticides and synthetic fertilizer from the fruit and vegetables he grows has helped scientists redefine what it means to cultivate rich, balanced soil. Before he developed a protocol for growing strawberries organically, farmers applied an insecticide, herbicide, and a fungicide at the beginning of the growing season, then replenished what they’d stripped from the earth with synthetic fertilizers. The fumigant sapped life from conventionally farmed fields.

Today, Cochran works with geneticists to identify microorganisms living in his soil that accelerate the turnover of nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium. Rich soil is no longer just a matter of plant nutrients. It’s also a measure of the health and diversity of microbes that help deliver the nutrients to each crop. Agronomists from Trace Genomics use DNA sequencers to identify microorganisms and recommend practices and products that boost the productivity of the soil.

“Without research to guide him,” says Samuel Fromartz, author of Organic, Inc.: Natural Foods and How They Grew, “Jim Cochran came up with precise methods for raising organic strawberries and proved that he could grow them commercially.” Conventional and organic strawberry farmers have adopted many of Cochran’s techniques for combining compost, cover crops, organic fertilizer, crop rotation, and integrated pest management to produce a berry that balances the fertility of the plant with the well-being of the planet. Together, these techniques increase productivity, resist drought and pests, and significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions, according to researchers from the University of California at Davis.

Beyond Organic

But Cochran set his sights well beyond discovering new ways to cultivate strawberries to restore the planet. Because muscular-skeletal injuries, not pesticide poisoning, is the most common occupational injury reported by farm laborers, he cultivates planting beds that crest 18 inches above the coastal terrace. The earthen mounds reach halfway toward his goal to eliminate stoop labor from strawberry fields.

Cochran’s willingness to innovate and commitment to basic research has changed the way farmers grow specialty crops in a state where one-third of all fruit and vegetables is harvested by hand. “We have taken research to Swanton Berry Farm,” Stephen Gliessman, professor of agroecology at the University of California at Santa Cruz, says, “and turned it into sustainable practices that all farmers can adapt to their own growing conditions.”

“I was searching for a way to ensure that fair labor practices became part of the company.”

Sharing the Bounty

If the USDA certifies the company’s farming methods, the United Farm Workers of America sanctions its labor practices. In 1998, after the UFW embarked on a bitterly fought campaign to organize strawberry workers at large conventional farms, Cochran’s collaborative approach to management produced the nation’s first agreement between an organic farmer and the labor union.

“I was searching for a way to ensure that fair labor practices became part of the company,” Cochran says. “The labor agreement preserves our commitment to job security, open communication, participatory management, mutual respect, and shared economic gains.” According to Philip Martin, professor of agricultural and resource economics at U.C. Davis, full-time field workers earn an average of $17,500 per year. The most recent labor survey reports that small and midsized organic farmers in the state offer workers modest fringe benefits.

Fieldworkers at Swanton Berry Farm earn as much as $35,000 a year with medical and dental insurance, vacation pay, holiday pay, family leave, and a union pension. Cochran offers these wages and benefits on the strength of the demand for his fruit and vegetables from customers who purchase produce at the farm and local markets. “They’ve bought as many strawberries as we can produce at a price that supports organic farming and a living wage for our employees,” he says.

For Good Reason

Workers from Swanton Berry Farm plant a variety of strawberry that is high in natural sugar and volatile oils. Its flavor peaks within days of harvest. “Strawberries do not ripen once they’ve been picked,” Cochran explains. “So we harvest them as close to dead ripe as possible. It’s much easier for growers to pick strawberries early to extend the shelf life of the berry,” he explains. “But there is an inverse relationship between shelf life and flavor.”

While some commercial growers place strawberries with a 17-day shelf life in cold storage before shipping them cross country, fieldworkers at Swanton Berry Farm load pallets of fruit directly onto trucks that whisk them to market within hours of harvest. Cochran’s fresh outlook on raising fruit and vegetables is not lost on the men and women who work his fields.

A quarter century after arriving in Davenport, Pedro Tortoledo has reason to celebrate. While a Mexican corporation planted and farmed sugar cane at his ranchero because his family could no longer afford to grow corn, prospects look good for him and the rest of the Swanton Berry Farm field crew. “My long-range plan,’ Cochran says,” is to give each employee a stake in the farm.”

Facebook: swantonberryfarm

Instagram: swantonberryfarm

Seasonal berries and vegetables are available from the farmstead:

Swanton Berry Farm

25 Swanton Road

Davenport, CA 95017

Or you can purchase them at the following farmers’ markets:

Berkeley (Tuesday and Saturday)

Marin (Thursday and Sunday)

Menlo Park (Sunday)

Noe Valley (Saturday)

San Francisco – Ferry Building (Saturday)

This article originally appeared in Issue 11.2 “Device”